Photography Story of the Last Craftsman "Gong Factory" in West Bogor District, Bogor City, West Java Province

Abdullah Syamil Iskandar | 2023

In the city of Bogor, there’s a historic place that many people have never heard of — it’s called the Gong Factory. This isn’t just any workshop — it’s believed to be the oldest gong factory in Indonesia, standing strong for over 370 years.

Located on Pancasan Street, the factory produces traditional gongs made of brass and metal, along with other Javanese gamelan instruments like bonang and saron. What makes it truly special is not just the age, but the craftsmanship passed down through seven generations of artisans. Behind every resonating gong is a story of heritage, skill, and a deep-rooted tradition that still lives on today.

The front yard of the "Gong Factory" in Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Tuesday, November 28, 2023. The space is rented out to street vendors as a way for the Gong Factory to earn additional income. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

This old factory building has stood the test of time — once surrounded by forest, it now sits in the middle of Bogor City, flanked by buildings and the busy main road, Jalan Pancasan. Just by looking at it, you can feel how much time has passed. The “Gong Factory” isn’t just a historic site — it’s also home to a long line of gong makers, now entering their seventh generation, led by Krisna Hidayat, the son of Haji Sukarna, who passed away in mid-2019.

Back in the 1980s, the factory saw its golden era with 20 young, skilled artisans working daily. But today, only six craftsmen remain. Age and time have slowly reduced their numbers. Since 2019, these six artisans have carried on the legacy — but no new generation has stepped in yet. As of now, the seventh generation might also be the last for the Gong Factory. Today, only six people are still actively working at the Gong Factory. Four of them are gong craftsmen: Hidayat (49), Acang (48), Didin (58), and Rasyid (47). The other two, Krisna (47) and Andy (68), serve as the factory’s leader and deputy.

Krisna and Andy don’t just handle incoming orders — they also coordinate the remaining craftsmen to manage production. And when things get busy or there’s a shortage of hands, they step in to help with the making too. The factory building they work in isn’t just a workspace — it’s a silent witness to the Gong Factory’s long journey. From deep forest to urban center, from its glory days to the challenges of modern times, the factory still stands strong. But with fewer and fewer artisans left, this treasured tradition now hangs by a thread.

Profile photo of Hidayat (left) and Acang (right), in Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Thursday, July 7, 2023. Hidayat usually burns the gong material (lakar) using a sledgehammer while Acang hits the gong material using a hammer. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

Profile photo of Rasyid (left) and Didin (right), in Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Thursday, October 5, 2023. Rasyid is usually the one who breaks and melts the damaged gong material to make a new gong material (lakar) while Didin hits the gong material using a hammer and tidies up the finished gong using a grinder. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

Rasyid passes a photo frame displayed in the living room of the “Gong Factory” factory and Krisna sits playing with a smartphone, in Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Thursday, October 15, 2023. The photo frame is a photo of the glory days of “Gong Factory” in the 1980s. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

Some young people have actually tried to become gong craftsmen, but most of them eventually choose to give up. The thing is, this job is not easy — it requires a lot of energy, the place is hot, and the constant sound of metal hitting can make your head spin. Plus, the wages often do not match the hard work. All of that is the reason why many end up not lasting long in this profession.

Profile photo of Krisna (left) and Andy (right), in Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Sunday, July 9, 2023. Krisna as the leader of “Gong Factory” and Andy as the deputy leader. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

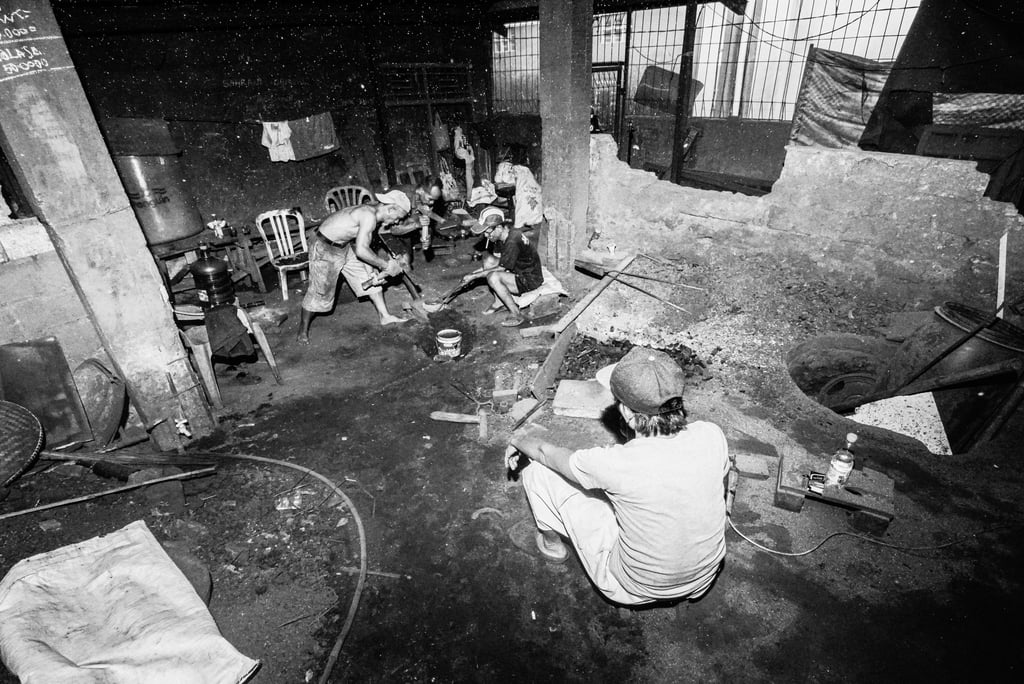

Craftsmen take turns beating the basic gong material (lakar) at the “Gong Factory”, Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Monday, May 15, 2023. The gong material is beaten until it forms a round gong, usually taking 2 hours. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

The decline in the number of craftsmen at the "Gong Factory" did not just happen. One of the main causes is dwindling income. For the craftsmen, the results they get now are far from enough. On the other hand, age is also an important factor — of the six remaining craftsmen, the average age is approaching 50 years, with the oldest being 68 years old. At this age, their strength is certainly not as strong as before, and the small number of craftsmen makes the work even harder.

What makes it even more complicated is that until now there has been no new generation ready to continue this tradition. The Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 also worsened the situation — orders decreased, income became thinner, and production became less frequent. Now, gong-making activities at the "Gong Factory" are no longer routine every day. The craftsmen only start working when an order comes in. If this condition continues, it is not impossible that this oldest gong factory will close, and the craftsmen will lose the only source of income they still rely on.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit Indonesia, the “Gong Factory” had to think hard to survive. One way: renting out its stalls and front yard to traders. Previously, the stalls were used for displays — a place to show off and sell the craftsmen’s work to visitors. The entrance route for tourists was through there, while the front yard became a parking area. But since gong orders dropped drastically due to the pandemic, the factory started renting out its spaces. Now, the stalls have been transformed into barbershops, and the front yard is filled with street vendors who sell every day. This method is a way for the “Gong Factory” to stay alive amidst difficult conditions.

This small alley next to the front yard is the main access to the factory entrance as well as the entrance to the residential area. When this project started, around January to March, the building on the left side of the photo was still empty and unfinished — just standing half-finished, abandoned. But from March to November, the building was completely transformed into a ready-to-use outlet.

This change shows how quickly time passes. In the past, "Gong Factory" stood in the middle of the forest. But now, the surrounding environment has developed into a dense building complex. Because of that, the factory finally moved to the middle of the residential area.

This alley is not only an entrance for craftsmen, but also an important route for residents to enter and exit the Pancasan area.

Didin carries a gong that has been tuned to sound carried through the side alley of the "Gong Factory", Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Tuesday, October 7, 2023. This alley is one of the roads leading to the factory entrance. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

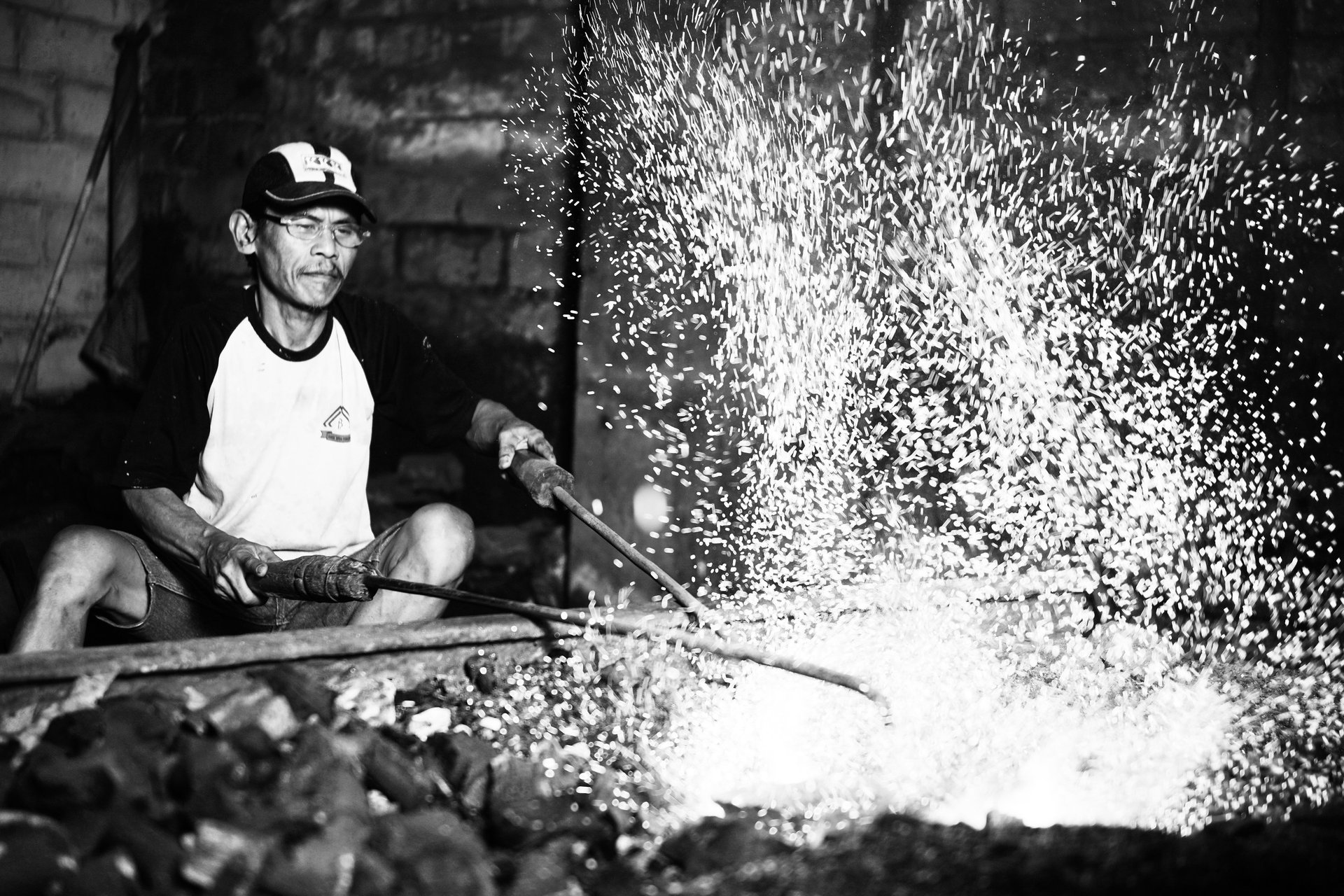

The process of burning the gong-making materials was carried out by Hidayat in the "Gong Factory", Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Monday, May 15, 2023. This burning process uses charcoal as fuel. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

In making gongs, "Gong Factory" uses charcoal as fuel. The choice of charcoal as fuel is based on its very affordable price and ease of combustion. The process produces sparks from the charcoal fire that spread in various directions, as seen in the photo on the right. To reduce the risk of charcoal splashes, Hidayat uses a pick to turn the gong material that is being grilled. The torch is a tool used to control the burning and rotating the gong (lakar) material over the charcoal. The tip of this baffle is bent, functions to pull, push and rotate the gong material so that the combustion can be adjusted according to needs. The handle of the insulator held by Hidayat is made of wood, so the heat from the tip does not sting his hand. This expertise in burning is Hidayat's specialty, and every time there is production, it is ensured that he takes care of burning the materials because of his long experience. Therefore, other craftsmen entrusted this task to Hidayat.

Conditions when the gong-making process is carried out inside the "Gong Factory", Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Saturday, October 7, 2023. The reason for the hot air temperature is due to the closed building design, which aims to prevent air from extinguishing the burning of charcoal so that the temperature remains stable. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

Dust from burning charcoal stuck to Hidayat's clothes at the "Gong Factory", Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Thursday, October 12, 2023. The effects of using charcoal as a fuel for making are causing minor burns if it comes into contact with the skin, dry throat and making hair coarse. Therefore, these craftsmen wear hats while working to protect their heads from charcoal ash. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

The atmosphere during the gong forging process inside the factory really feels hot. The high temperature comes from the burning of charcoal, while the factory building itself is tightly closed, with minimal air ventilation. Because the design is made that way — the goal is to prevent outside wind from entering and extinguishing the burning fire. However, the effect is that the heat is trapped inside the room.

Inside the room, fine dust from the charcoal can also be seen floating on the ceiling. Because of the lack of air circulation, the dust just swirls around inside. The atmosphere feels increasingly heavy, hot, and stuffy.

In the left corner of the photo, a gallon of drinking water is always ready. The craftsmen here must drink diligently to fight dehydration. Working in high temperatures and dusty air makes the body tire quickly, so water is their main savior during the work process.

The remaining dust from the charcoal burning process is still clearly visible around the work area. The charcoal that is the main fuel not only makes it hot, but also has a direct impact on the craftsmen. Sometimes it can cause the skin to blister if it is exposed to hot sparks, make the throat dry, and hair become rough because it is constantly exposed to dust.

To overcome this, the craftsmen usually wear hats so that their heads are not directly exposed to the ash flying around in the room. Meanwhile, for dry throats, they routinely drink mineral water to help neutralize the charcoal dust inhaled while working.

Rasyid is peeling a banana at the “Gong Factory” factory, Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Saturday, July 7, 2023. Bananas are the perfect snack because they can add energy in the middle of work. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

Right Photo: Krisna is adjusting the sound of the saffron musical instrument using a keyboard application on his smartphone, in the living room of the "Gong Factory", Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Sunday, July 8, 2023. Not only the application on the smartphone but also the adjustment using a tool called a rotary pitch instrument used by Didin in the left photo. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

This photo captures the moment when Rasyid is peeling a banana. Both of his hands are visible — his right hand is wearing a cloth glove, while his left hand is left open. This right hand is the one that works the hardest. With this hand, Rasyid hits the gong material using a heavy hammer. Because it is used so often, his palm is often scratched, even injured. Gloves are worn to reduce friction, although they still do not completely protect.

Meanwhile, his left hand only functions to support the weight of the hammer when it is swung. Black dust from burning charcoal sticks between his nails — a typical trace of work in a factory.

In the midst of heavy physical work, craftsmen like Rasyid need extra energy. Bananas are their mainstay snack — cheap, easy to eat, and they can immediately continue working without much interruption.

Didin (left) and Krisna (right) are tuning the sound of the bonang and saron using modern tools. In the left photo, Didin is seen adjusting the tone of the bonang with the help of a wind instrument called a rotary pitch instrument. He blows a certain tone, then matches it with the sound of the bonang until both are in harmony.

Meanwhile, in the right photo, Krisna uses a keyboard application on his smartphone to determine the tone. The process is similar — the tone of musical instruments such as the bonang, saron, or gong is matched with the sound in the application. If it is not right, they will retune it until the tone is exactly right.

In the past, before there was sophisticated technology, all processes were done manually — they only relied on instinct and sharp ears. Tuning the gong sound was not a trivial job, and the only one who could do it at that time was H. Sukarna, the sixth generation leader at the "Gong Factory".

Unfortunately, that special ability was not passed on to the next generation. But times are changing. Now, craftsmen are starting to adapt to technology — using applications on smartphones to help arrange gong tones. From the old way to the new way, tradition continues while following the times.

Equipment for making gongs that has existed since the first generation and is still used today, the seventh generation, at the "Gong Factory", Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Sunday, May 28, 2023. The equipment consists of a hammer, tongs, a ruler, and a chisel.

This equipment is one of the proofs that “Gong Factory” has indeed been established for a long time. Tools such as hammers, tongs, gongs, and penyingen have been around since the first generation and have continued to be used from generation to generation until now — the seventh generation. In this photo, you can see directly the traditional equipment used to make gamelan musical instruments from metal and brass. Amazingly, even though they are tens or even hundreds of years old, these tools can still be used well. That is proof that from the beginning, they have used the best materials — because quality never lies.

From left to right: Didin, Rasyid, Acang, Hidayat, Krisna and Andy (sitting) pose inside the “Gong Factory”, Pancasan, Bogor City, West Java Province, Saturday, October 7, 2023. Abdullah Syamil Iskandar

The last generation of craftsmen took a group photo — this moment is important evidence that there is still some spirit left from the glory days of the “Gong Factory” in the 1980s. This story is a reminder that times are constantly changing. Technology is getting more sophisticated, humans are moving forward, and everything is shifting — including the fate of the “Gong Factory” in Bogor City, West Java.

Through these photos and stories, it is hoped that the public can learn about and become familiar with the cultural heritage that is almost lost. Because it could be that in the next 15 or 20 years, if there is no young generation ready to continue, these last craftsmen will slowly disappear — not because they are forgotten, but because time cannot be stopped.

Through these images and stories, I hope to share a glimpse into the fading rhythm of tradition that still echoes within the walls of the Gong Factory. May this legacy continue to resonate — if not in sound, then in memory.